One of the assaults that has been forwarded with much success against traditional Judeo-Christian suppositions has been the slow eating away of various aspects of the Biblical account of the beginning, contained within the Book of Genesis. Evolutionary biology and geology have since the 19th century dethroned any idea that the world was created in a six-day period as Genesis 1 seems to claim. Our study of genetics has debunked the notion that the human race is descended from two people named Adam and Eve. Our broader account of history has thrown away any idea of a worldwide flood from which only a small family of humans and a whole lot of animals survived. Most importantly, our knowledge of the ancient world, furthered by new efforts in archaeology, have disenchanted a number of the early Bible stories, showing many parallels to them in Sumer and Babylon that seem to make them less an exclusive display of divine inspiration and more ordinary fare in the Ancient Near East.

It is my proposal that this is because the opening stories of Genesis (chapters 1 through 11) are not important in so far as they relate to us particular events in history but because they impart to us thought-provoking lessons about our world and because they tell lasting truths about who we are as human beings. The genius of the first chapters of Genesis is not in that they are exclusive revelations to humanity from the divine but that they are the product of a certain group of authors who saw many important insights into who we are as people and used the toolkit provided by their cultural and religious heritage to put these insights into the form of narrative, one which the careful reader can spend long periods of time trying to fully appreciate: they tell us about something about ourselves, our relationships, and our collective human nature. This is the true value of Genesis 1-11.

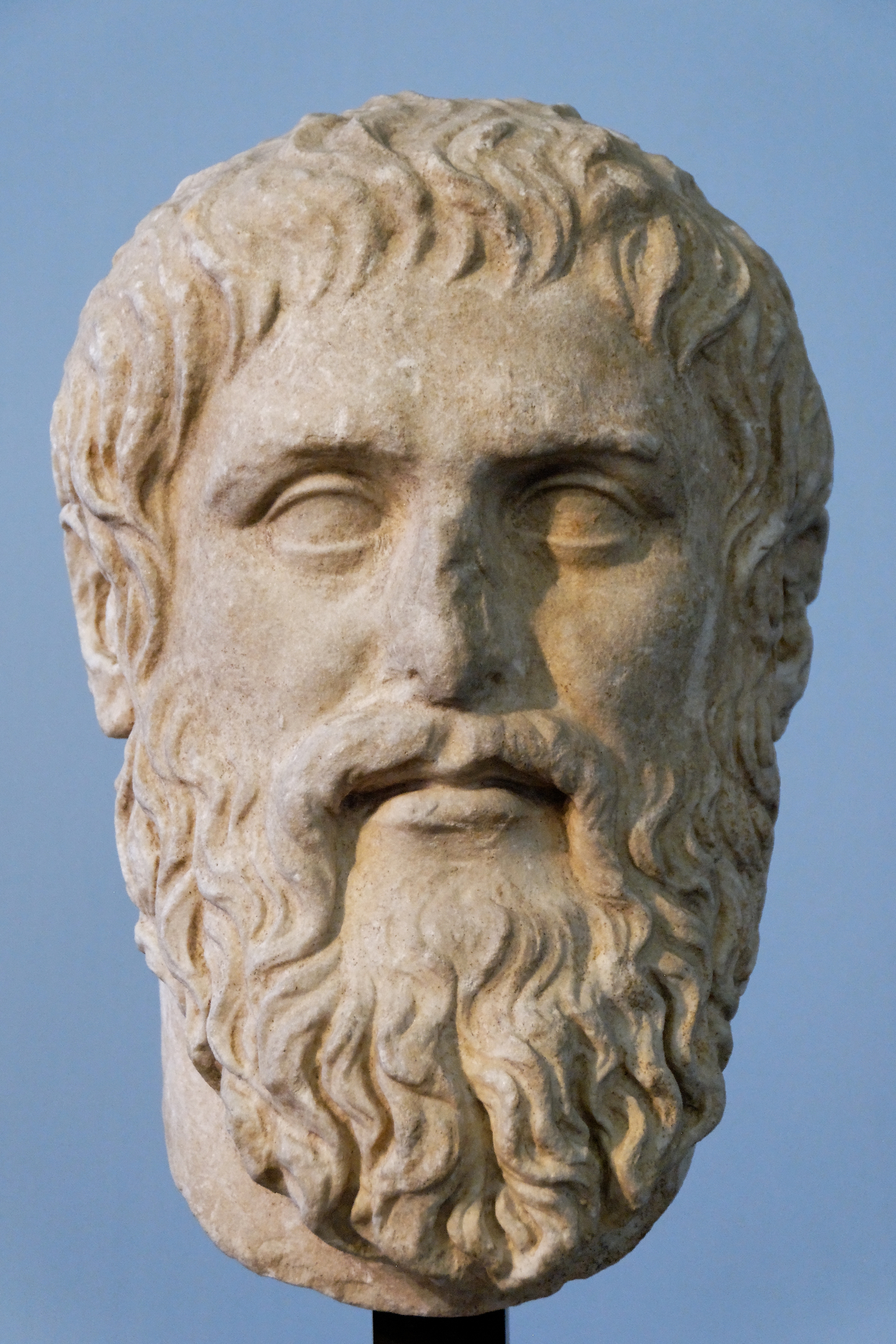

When one looks for example at the seven-day creation story given in Genesis 1, we do not find a story informed by any science about how our world actually came into being. The writers had no knowledge of the Big Bang, of evolution, and of Earth's tininess within the cosmic picture. We do however find that the authors bring to the table a unique vision (however questionable its philosophical presuppositions might be) of how the created order of the universe is. In Genesis 1, we are treated to a play in which humankind is the climax, in which there is a carefully considered order and symmetry to the creation (displayed through the symbolic layout of the days themselves), in which the idolatries common to humankind's religious accountings of the cosmos are attacked (our natural worship of the heavens), and which plays with our sense-perceptions to rework our unguided presuppositions about the world.

Just after this tale of cosmic creation, we are brought to a new scene, this one centered around the Garden of Eden. This story is yet another creation tale:

intentionally juxtaposed by Genesis's writers to give yet another account of beginnings. This one addresses less the relation between man and the created cosmos as the first one did but focuses on the necessary plight of humans as they rise from blissful ignorance to the pained self-awareness that comes with being the rational and civilized but desirous and self-aware animal. The story of Adam and Eve enjoying a blissful nude life being destroyed when Eve eats of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, leading to their banishment from the Garden, shows the necessary but damaging process that the heightened consciousness of mature civilized life can bring. More in line with traditional faith, it polemicizes against the primeval human sin of hubris. Aside these more central themes, there arises themes of what the text sees as the primeval human relationship: the sexual relationship between man and woman. It is some story which can include the dialectical tension between childlike blissful ignorance and mature civilized awareness, the inherent nature of human hubris, and the nature of the man-woman sexual relation all in one movement. This, rather than any claims to historical fact, is where the genius of Eden resides.

We then leave from Eden to visit their children Cain and Abel, whose sibling rivalry leads to fratricide. Just after the Eden story shows us the sexual relationship between man and woman, this story provides the relation between brothers, one the text sees rooted in inherent conflict. Between the lines also lies more commentary on the lessons of human life. This between the lines commentary can be even more be glimpsed in the seemingly meaningless genealogies, which show us the greedy exploits of the violent children of Adam.

As we plot through these genealogies detailing the violent excesses of Adam's descendants, we arrive at the story of Noah and his ark. However ostensibly barbarous God's actions might be in wiping out all life on Earth through flood, the story does illustrate the continued Biblical theme of deliverance from evil, of renewal, of the continuance of life and God's promise, as well as a polemic against the numerous other mythological traditions in the Near East with flood myths. In this flood story, the Genesis writers can articulate much of their view about God, man, and the world through a common myth.

The interactions of Noah with his family after the events of the flood also provide the first insight not simply into the relations of man and woman or of brothers but of the relations of the entire family. The story of Ham's humiliation of his father, the curse of Canaan, and the honor held to Shem and Japheth serve to illustrate compelling points about the relationship between fathers and sons when read closely.

Finally, we finish with the Tower of Babel, which sees the creation of a monument to human hubris- as man seeks "to make a name for themselves" by creating a towering city where technical prowess exceeds moral piety- "This is only the beginning of what they will do- nothing that they will propose will be impossible for them" (11:6) and where the humbling and sobering contours of the human spirit are ignored in favor of a potentially destructive arrogance. The debates centered around

transhumanism and the relationship between science and morality already occur in these pages, long before the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment brought them to the center of Western man's affairs.

All of these stories leading up to the main tale of Abraham and Israel are themselves derivations of various tales from the Near East. The seven-day creation tale mirrors many aspects of Babylonian creation myth. Stories abounded in Ancient Mesopotamia about serpents, paradises, and Trees of Life. Genealogies were common as mythical accounts of a civilization's credibility at that time. The Flood story with Noah stands in a long line of other flood stories, most notably the earlier one contained in The Epic of Gilgamesh. The Tower of Babel was in all likelihood a simple ziggurat built by either the Babylonians or the Assyrians.

None of these stories have supernatural origins. They all descend from traditions common in the Near East. They were written in an era where scientific ignorance about the world was immense. However, that is not where these stories shine. They shine in what the authors of Genesis did know a thing or two about- they shine in asking us deep questions of spirituality and anthropology, of human life and human nature. Whether we agree with them or not (this author has plenty of reservations), they use narrative in such a way to get us talking, thinking, and if we're people of faith, praying.

In these early pages in which The Bible lays out the unaided human condition before God's intervention with Abraham, commentary is given on the nature of human relationships, the nature of the cosmos, the nature of heroism and vanity, and even the relationship between science and morality among many other things. Whatever one's opinions might be, learning these pages and engaging with the deep questions these seemingly simple texts pose can help one be a much more informed and enriched human being.

(Note: Much credit for the interpretations of the first pages of Genesis here must be given to thinkers such as Leon Kass in his amazing book "The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis" and the numerous other OT scholars and thinkers who have put in far more time than the author to deciphering these early chapters of The Bible. Their writings on Genesis have inspired the author in his thinking on Genesis immensely and they must be thanked for their scholarly insights into The Bible. I could not have proved my point about Genesis's insights without their help.).

_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg/1280px-Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_The_Tower_of_Babel_(Vienna)_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg)